Believe It or Not

Ausstellung So., 19.05.2013–So., 11.08.2013

Lesedauer etwa 18:26 Minuten

19. Mai bis 11. August 2013

Ausstellung der Stipendiaten des 18. Internationalen Atelierprogramms der ACC Galerie und der Stadt Weimar:

sowie der HALLE 14 – Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst Leipzig:

[show english version]

Ausstellung vom 19. Mai bis 11. August 2013

Stipendiaten des 18. Internationalen Atelierprogramms der ACC Galerie und der Stadt Weimar:

Ana Mendes (PT) | Shiblee Muneer (PK) | Naufús Ramírez-Figueroa (GT)

sowie der HALLE 14 – Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst Leipzig:

Txema Novelo (MX) | Chan Sook Choi (KR)

Eine Koproduktion von Stadt Weimar und ACC Galerie Weimar. Mit Unterstützung durch das Thüringer Ministerium für Bildung, Wissenschaft und Kultur, die Sparkasse Mittelthüringen und den Förderkreis der ACC Galerie Weimar.

Fünf Künstler von drei Kontinenten befassen sich mit Fragen um Gott, das Göttliche, Religion, Spiritualität und Glauben.

Ana Mendes aus Portugal, Naufús Ramírez-Figueroa aus Guatemala und Shiblee Muneer aus Pakistan waren Stipendiaten des 18. Internationalen Atelierprogramms „What Happened to God?“ („Was ist mit Gott passiert?“) der ACC Galerie Weimar und der Stadt Weimar im Jahre 2012, lebten und arbeiteten für je vier Monate im Städtischen Atelierhaus. Die Arbeitsergebnisse und weitere ihrer Arbeiten werden in der Ausstellung „Believe It or Not“ („Ob Du’s glaubst oder nicht“) vorgestellt. Dazu gesellen sich Chan Sook Choi aus Südkorea und Txema Novelo aus Mexiko, die am Stipendiatenprogramm der Partnerinstitution des ACC, dem Leipziger Zentrum für zeitgenössische Kunst HALLE 14, teilnahmen, das ebenfalls zu „What Happened to God?“ ausgetragen wurde.

Programm „What Happpened to God?“ | Konzept „Believe It or Not“

Ob wir an einen Gott glauben oder nicht – unsere Welt wird tiefgreifend von Ideen um Gott und das Göttliche beeinflusst. Die Vorstellung des Göttlichen, Absoluten und das menschliche Streben, sich mit einer „höheren Macht“ in Einklang zu bringen, sie zu einem Bild des transzendenten, guten Schöpfers zu verdichten, um über dessen kollektive Verehrung Schutz, Trost und Glück zu finden, aber auch um Herrschaftsverhältnisse abzusichern, sind so alt wie die Mensch-heit. Warum verhindert oder lindert ein höheres Wesen nicht Leiden und Unglück auf der Welt? Diese zentrale, kritische Frage, die seit Anbeginn der Religionen Gläubige wie Nichtgläubige beschäftigt, findet ihre (vorläufige) Zuspitzung in der Formulierung, dass Gott stets einer ist, der Auschwitz zugelassen hat.

Die sich zuspitzenden Problemstellungen des 21. Jahrhunderts, wie religiöse und ethnische Konflikte und Terrorismus, der Kampf um Naturressourcen (und damit verbundene Armut und Hungerkatastrophen), die Globalisierung und der Mangel an rationalen Lösungen zur Rettung der Welt scheinen einerseits zu korrespondieren mit einer erhöhten Glaubensbereitschaft, mit einer gesteigerten Bindung an verschiedene Religionskulturen, mit einem teils fanatischen, radikalisierten Festhalten an Glauben und Religiosität. Andererseits sind Abkehr von der Kirche, Glaubensdefizit und Glaubensmissbrauch keine Seltenheit, verlieren Menschen ihren Glauben, geben sich anderen Formen der Spiritualität hin, suchen nach neuen Inhalten für ihr Leben, an denen festzuhalten erstrebenswert scheint. Offenbar ist der Mensch ohne Glauben kein Mensch.

Dennoch wird die Religion als „Seufzer der bedrängten Kreatur“, „Gemüt der herzlosen Welt“, „Geist geistloser Zustände“ und „Opium des Volkes“ (Karl Marx), aus der man sich zu höherem Menschsein nur durch totales Abstreifen des abendländischen Christentums mit einer „Umwertung aller Werte“ (Friedrich Nietzsche) aufschwingen könne, ebenso kritisiert, wie die Glaubenskultur schlechthin von zahlreichen Wissenschaftlern, Historikern, Psychologen und Völkerkundlern angefochten wird, die im zurückliegenden Jahrzehnt jegliche Formen von Religion, Irrationalismus, Aberglaube und Pseudowissenschaft ablehnten und sich für eine von Vernunft und Verstand anstelle von religiösem Hass und Irrationalismus dominierte Welt einsetzten.

Jene, die sich zum traditionellen Glauben bekennen: Was haben sie gefunden? Und jene, die sich neu auf die Suche machen: Wonach trachten sie? Eint beide die gemeinsame Vorstellung von einer gemeinschaftlichen Utopie des Paradieses auf Erden? Teilen sie dasselbe Dilemma von der Unauffindbarkeit dieses Ortes, während sie in verschiedenen Flucht- oder Kulminationspunkten ihr Heil suchen? Was kann Gott ihnen bieten? Was ist mit Gott passiert in einer Welt, in der sich viele desillusioniert von ihm abwenden, andere ihn nur mit Gewalt zu verteidigen wissen, wiederum andere sich in Angst und Schrecken abkehren und die zur Gewohnheit gewordenen Bilder religiös motivierter Gewalt zwar konsumieren, aber ignorieren? Künstler zu sein, das Bekenntnis zur Kunst auszuleben, heißt das nicht auch, wie ein praktizierender Gläubiger, ein Mönch, zu agieren, mit dem Ziel, dem eigenen und dem Leben der Anderen neue Inhalte zu geben? Kennt Kunst Antworten auf die Frage: What Happened to God?

Internationales Atelierprogramm der ACC Galerie Weimar und der Stadt Weimar

Die Stadt Weimar als Mitinitiatorin und Partnerin des Internationalen Atelierprogramms verfolgt das Ziel, Künstlerförderung und Präsentation zeitgenössischer Kunst im Stadtraum miteinander zu verknüpfen, als Treffpunkt und Forum für Künstler zu wirken und internationale Beachtung zu finden. So sollen der internationale Kulturaustausch gefördert und Vorurteile abgebaut werden. Die Stadt Weimar unterstützt das Programm, indem sie u.a. ein Atelier mit angeschlossenem Appartement im Städtischen Atelierhaus Weimar – einem der ältesten Gebäu-de dieser Art in Deutschland – zur Verfügung stellt und ¾ des jeweiligen Monatsstipendiums von 1.000 Euro finanziert. Mittel für das restliche Viertel wirbt die ACC Galerie Weimar ein, die das weltweit wirkende Bewerbungsprocedere organisiert, die unabhängige Jury einberuft und die Künstler ganzjährig betreut.

Am 5. und 6. November 2011 wählte eine Expertenjury, bestehend aus dem Berliner Kunstkritiker Peter Herbstreuth, Jean-Baptiste Joly, dem Direktor der Akademie Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart, der in Berlin und Wien lebenden Künstlerin Johanna Kandl, Kai Uwe Schierz, dem Direktor der Erfurter Museen und der finnischen Kunstkritikerin und Kuratorin Marketta Seppälä, die Stipendiaten für das Internationale Atelierprogramm aus.

Das „Internationale Atelierprogramm der ACC Galerie und der Stadt Weimar“ wurde 1994 ins Leben gerufen. Bisherige Jahresthemen: „Allegorien“ (1995), „Fascis – Faschismus und Faszination“ (1996), „Kopf an Kopf – Head to Head – Tête à Tête“ (1997), „Gemeinschaft – Gesellschaft“ (1998), „Hautnah“ (1999), „Herzblut – Schriftbild“ (2000), „Das Maß der Dinge“ (2001), „über MENSCHEN – Zur Zukunft des Humanen“ (2002), „herkunft niemandsland“ (2003), „Die Ironie ist tot. Es lebe die Ironie!“ (2004), „Die Kultur der Angst“ (2005), „Die Subversion des Stillstands“ (2006), „AUSSEN VOR“ (2007), „Von der Unbestimmtheit“ (2008), „Kunstfehler – Fehlerkunst“ (2009), „Jenseits der Sehnsucht“ (2010), „Über den Dilettantismus“ (2011) und „What Happened to God?“ (2012) und „Mit krimineller Energie – Kunst und Verbrechen im 21. Jahrhundert“ (2013). Die bisherigen 57 Teilnehmer des Programms kamen aus: Argentinien, Australien, China, Deutschland, Finnland, Griechenland, Großbritannien, Guatemala, Irak, Irland, Israel, Italien, Japan, Kanada, Kroatien, Kuba, Mazedonien, den Niederlanden, Norwegen, Pakistan, Portugal, Russland, Schweden, der Schweiz, Serbien und Montenegro, Slowenien, Spanien, der Türkei, Uruguay und den USA.

[deutsche Version anzeigen]

Exhibition from May 19th to 11th of August, 2013

Resident of the 18th International Studio Program hosted by the ACC Galerie Weimar and the City of Weimar:

Ana Mendes (PT) | Shiblee Muneer (PK) | Naufús Ramírez-Figueroa (GT)

and the International Fellowship Programme Studio14 hosted by HALLE 14 in Leipzig:

Txema Novelo (MX) | Chan Sook Choi (KR)

A cooperation by the City of Weimar and the ACC Galerie Weimar. Supported by the Thuringian Ministry of Education, Science and Culture, the Sparkasse Mittelthüringen and the sponsors’ association of the ACC Galerie Weimar.

Five artists from three continents look at questions of God, the divine, religion, spirituality and faith. Ana Mendes from Portugal, Naufús Ramírez-Figueroa from Guatemala and Shiblee Muneer from Pakistan were residents of the 18th International Studio Program “What Happened to God?”, held by the ACC Galerie Weimar and the City of Weimar in 2012. The artists lived and worked in the Municipal Studio Building for four months each. The results of this time, as well as other works by the artists, are presented on the occasion of the exhibition “Believe It or Not”. Joining these artists are Chan Sook Choi from South Korea and Txema Novelo from Mexico, who took part in the International Fellowship

Programme Studio14 at HALLE 14 Centre for Contemporary Art, ACC’s partner institution in Leipzig. There the artists dealt with the question “What Happened to God?” as well.

Whether we believe in a god or not, our world is profoundly influenced by concepts of god and the divine. The image of the divine, the absolute and the human pursuit to bring oneself in harmony with a “higher power,” condensing these things into an image of a transcendent, benevolent creator, using these things to find protection, solace and happiness through collective worship, but also to maintain relationships of power, are as old as humanity itself. Why doesn‘t such a higher consciousness prevent or relieve suffering and misfortune in the world? This central, critical question that has occupied believer and non-believer alike since the beginning of religion finds its culmination in the formulation that it is God who allowed Auschwitz to happen.

The urgent issues of the 21st century – religious and ethnic conflict, terrorism, the struggle over natural resources (and the associated poverty and famine), globalization and the lack of rational solutions to save the world – on the one hand, appear to correspond to a heightened religious awakening, to a growing commitment to other religious cultures, to a partially fanatical, radicalized adherence to faith and religiousness. On the other hand, renunciation of the church, lack of belief and misuse of belief are no rarity. People lose their faith, dedicate themselves to other forms of spirituality and search for new meaning in their lives that seems worth holding onto. It seems that the person without belief is not truly human.

Nevertheless religion becomes “the sigh of the oppressed creature,” “the heart of a heartless world,” “the soul of soulless conditions” and “the opium of the people” (Karl Marx), and one can reach a higher level of humanness through completely stripping away western Christianity with a “transvaluation of all values” (Friedrich Nietzsche), by criticizing it just as the culture of belief itself is contested by numerous scientists, historians, psychologists and ethnologists – those who in past decades rejected any form of religion, irrationalism, superstition or pseudo-science and lobbied instead for a world that is dominated by rationality and intellect in lieu of irrationality and religious hatred.

Those who count themselves among the faithful: what have they found? And those who look for something new: what do they aspire to? Does a shared vision of a utopic Paradise on Earth unite them? Do they share a common dilemma of the untraceableness of this place, while they search for their salvation in different vanishing points? What does God offer them? What has happened to God in a world in which the disillusioned abandon him, others know only to defend him with violence, and yet others turn away in anguish and horror, and consume, but still disregard, the images of religiously motivated violence that have become commonplace?

To be an artist, to live out a commitment to art, does this not also mean to be a practicing believer, a monk, to operate with the goal of giving new meaning to one’s own life and those of others? Does art know the answer to the question: What Happened to God?

International Studio Program of the ACC Galerie Weimar and the City of Weimar

The City of Weimar pursues the following aims in its role as an initiator and partner of the International Studio Program: To combine financial support for artists with the presentation of contemporary art in the urban realm, to serve as a forum for artists and as a catalyst for encounter between them and to gain international recognition for the resulting activities. By these means, international cultural exchange is to be promoted and prejudices eliminated. The support provided includes the provision of a combination artist's studio/apartment in the Municipal Studio Building – one of the oldest buildings of its kind in Germany – and by financing ¾ of the monthly stipend of 1000€. ACC Galerie Weimar organizes the rest of the financing as well as the worldwide advertising of the call for entries, the annual selection process and jury meeting and looks after the artists during their stay.

On November 5th and 6th 2011, a jury of experts selected the residents of the 18th International Studio Program: Peter Herbstreuth, art critic from Berlin; Jean-Bapiste Joly, director of the Akademie Schloss Solitude in Stuttgart; Johanna Kandl, artist; Kai Uwe Schierz, director of the Erfurt Kunsthalle and Marketta Seppälä, Finnish curator.

The International Studio Program of the ACC Galerie and the City of Weimar was founded in 1994. Annual themes of the program have been: "Allegories" (1995), "Fascis – Fascism and Fascination" (1996), "Kopf an Kopf – Head to Head – Tête à Tête" (1997), "Community – Society" (1998), "Close to the Skin" (1999), "Heart’s Blood – Hand-Written Script" (2000), "The Measure of Things" (2001), "über MENSCHEN – The Future of the Human" (2002), "Origin – No Man’s Land" (2003), "Irony is dead. Long live Irony!" (2004), "The Culture of Fear" (2005), "The Subversion of Standstill" (2006), "ON THE OUTSIDE" (2007), "On Indefiniteness" (2008), "Failed Art – The Art of Failure" (2009), "Beyond Desire" (2010), “On Dilettantism” (2011), “What Happened to God?” (2012) and “With Criminal Energy – Art and Crime in the 21st Century” (2013). The 54 participants of the program have come from Argentina, Australia, Canada, China, Croatia, Cuba, Finland, Germany, Great Britain, Greece, Guatemala, Iraq, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Japan, Macedonia, The Netherlands, Norway, Pakistan, Portugal, Russia, Serbia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Turkey, Uruguay and the United States.

Using his own experiences as a basis, Naufús Ramírez-Figueroa, a Guatemalan artist living in Vancouver, Canada, examined the significance of religion today. The video-, installation- and performance-artist is the son of a former guerilla fighter in the Guatemalan civil war (1960-96), which was initiated by the USA in 1954 to prevent a perceived communist threat from Central America. Figueroa’s artwork reflects the events of his childhood, such as political violence and experiences as a refugee in Canada. Poetry, folklore, homosexuality, the politics of food and magical practices are often additional themes.

In Buchenwald Naufús Ramírez-Figueroa – himself as a survivor of a genocide – created a sonorous though speechless filmic work where his own voice is essential. “Artifacts of Language” (2012-2013) is a video installation composed of eight TVs, arranged in a curve, showing short clips of views in and around Buchenwald. In each filmed sequence, Ramírez-Figueroa shouts out abstract syllables like “eau”, “bo”, “la”, “currrr” or “sha”, while he himself remains invisible. He films this attempt at contact as well as its echo, pointing out the end of language and the (individual) inability and impossibility of describing the human act of violence – a return to childlike language: “I shout at the forests, because they are the ones who are the witnesses. The forests, who want to remember. All of this is linked to my personal experiences as a child when I was witness to violent acts and my inability to assimilate all the images and thoughts.” Action and “plot” change constantly during the videos; Naufús Ramírez-Figueroa uses film fragments of one second each to transform his shouting into a rhythmic beat.

The video “Caldo de Zopilote” was created in Guatemala in 2012 and shows the artist cooking a soup from the meat of a dead turkey buzzard he found. The relationship in which the buzzard normally eats human carrion is reversed. In Guatemala, the buzzard is a metaphor for many things; in this video the buzzard stands for a militarized enclave of power, which persists thanks to poverty, fear and inequality in the country.

In May 2013, José Efraín Ríos Montt, dictator and president of Guatemala from 1982 until 1983, was sentenced to 80 years imprisonment for genocide and crimes against humanity. Conservative members of Guatemalan society continue to deny the genocide that Guatemala experienced during the civil war. They say “genocide” was something that happened in Germany or Rwanda, but not in Guatemala. Their motto is “We Guatemalans are not a nation of genocide. There was no genocide.” As a counteraction, many survivors of the war and the massacres have developed their own motto: “Sí Hubo Genocido” / “Yes, there was genocide”. Naufús Ramírez-Figueroa, himself a victim of the genocide, brings this motto to the gallery – printed on a banner, flanked by found documentary photos of genocide deniers.

The prints for “Forest Road” (2012) come from five photographs shot with long exposures from a moving vehicle on the road to Buchenwald. This series was created to reflect on the meaning of visiting as a tourist a memorial like Buchenwald, a place charged with pain and suffering of the past. How do we approach such a place? Do we quickly pass by in tourist busses, while nervously und indifferently pressing the shutter release of our camera? The forest still contains life that has become abstract and that has its own message to communicate – despite our own approach, or our attitude and way of perceiving.

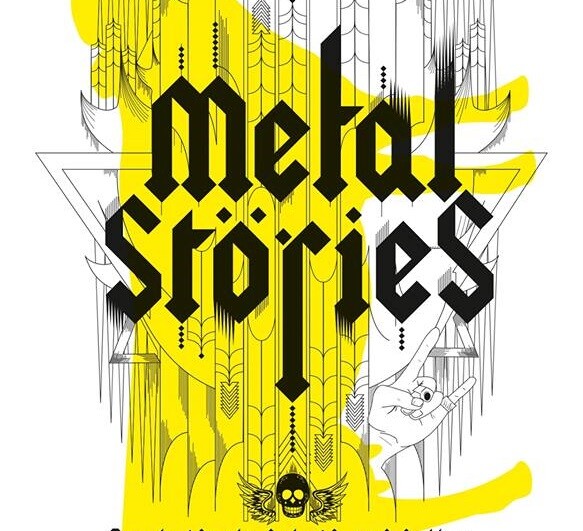

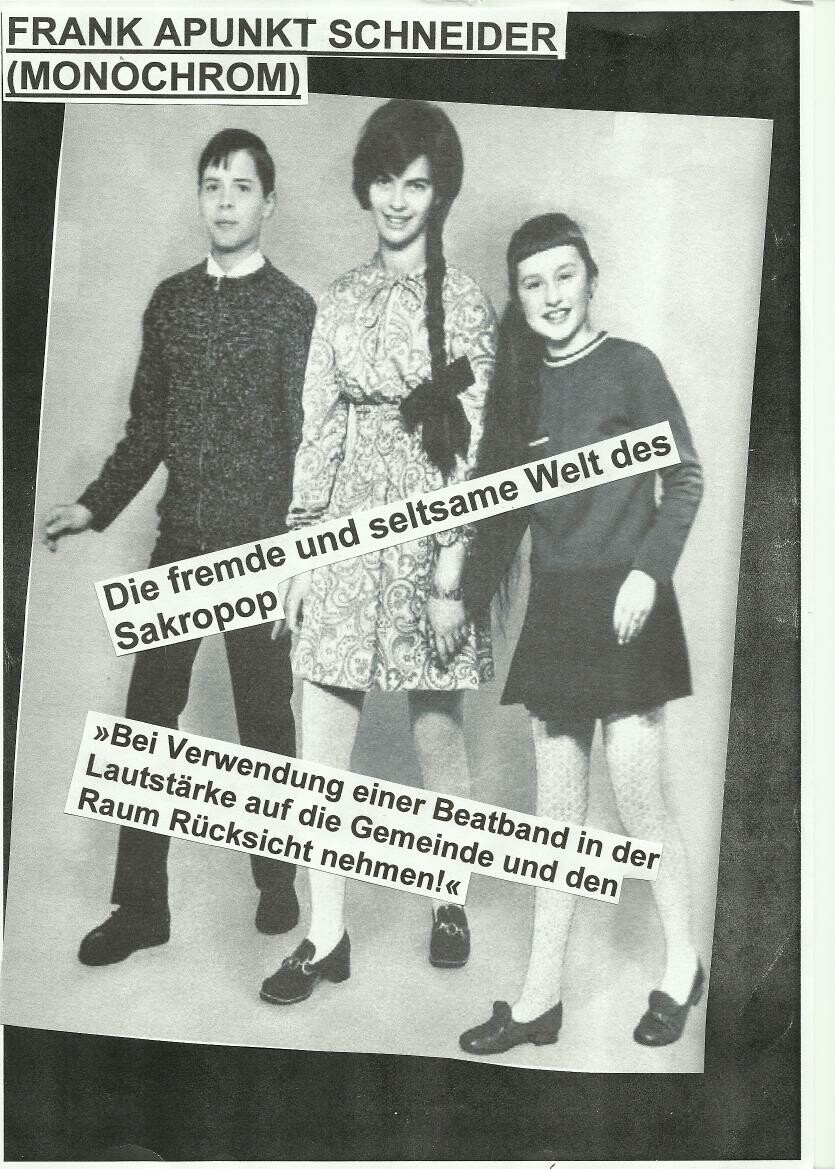

The Mexican artist Txema Novelo calls himself a Phrist – a form of pop occultism similar to that of Genesis P-Orridge, the scandalous artist and one of the inventors of industrial music. A Phrist should not be equated with a "pop Christian", but is rather a person who considers spiritual elements in human creations as part of the divine. Novelo firmly believes that rock 'n' roll and art are disciplines that unify human beings with God – even if only for an instant. Novelos' universe revolves around films, album covers, old and new myths; his thoughts are engaged in dialogue with persons like the philosopher Giordano Bruno, the Welsh Rosicrucian Dion Fortune, the beatnik Brion Gysin, the artist Joseph Beuys, the pop musicians David Bowie and Nick Cave, the alternative rock band Spacemen 3, the media artist and videogame programmer Toshio Iwai, cymatic sound patterns, sacred geometry, Final-Fantasy-videogames, etc.The film recently created by the Mexican artist is entitled “STILL MOVIE”. Divided in five, chronologically arranged chapters, “STILL MOVIE” is based on the idea of Gnosticism – that a human being is divine by nature, but divided because of the illusion of the "world". This image – recurrent in the artist's work – is called the "Joy Division/Sad Divine"-concept. The chapter "Division" treats this subject extensively. The five chapters of the film can stand alone, but the film is perceived as a whole – a development from the division to the divine.

Walter Schmidt Ballardo is an iconic figure of the Mexican New Wave/Punk underground scene of the 1980s; he was the son of a Mexican mother and a SS-soldier who had fled to Mexico. His contributions to a young and alienated scene were highly emblematic and found expression in his two bands at that time: SIZE and CASINO SHANGHAI. In “STILL MOVIE”, Ballardo plays a master painter, who must take an elixir from the distillate of a flower in order to keep himself alive; however, only his apprentice knows how to find the flower and to distill the elixir. Tired of this constant and exhausting exercise, the apprentice finds a way to free himself.

In the first room dedicated to Txema Novelo, you'll find the first four chapters of “STILL MOVIE”, which were shot in Mexico City, Los Angeles and Berlin during a four-year time span and supported by the Biennale Mexico-California 2010 and HALLE 14 in Leipzig.

Inspired by a letter of Friedrich Nietzsche to his friend Peter Gast, the 5th and final chapter of “STILL MOVIE”, entitled "In geistiger Umnachtung" (In mental derangement), will be finished this year. Parts of the film were shot in the Nietzsche-Archive in Weimar (supported by the Weimar Klassik Stiftung and the ACC Galerie Weimar) and in the Ethnobotanic garden in Oaxaca, Mexico.

In the following room you'll discover the first sketches and documentation for this last chapter: a video documentation of the frieze at the archeological site MITLA, the most important site of the Zapotecan culture in Oaxaca, Mexico, and a sequence of the video-synthesizer “Atari Video Music”, which creates images using the song “Hommage”, performed by the Mexican band Casino Shanghai (from their album FILM NOIR, 1985).

Ana Mendes is a multi-disciplinary artist and dramatist coming from Lisbon but living in London. She combines video, sound, photography and text in order to create projects dealing with subjects like otherness, identity and suppression. When working on the question "What happened to God?”, she spoke mainly to immigrants in Weimar und asked them about their feeling and sense of otherness and spirituality. Her project "This is my God" (in film and photography) aims to portray immigrants to Germany and to study "German identity" from their perspective. Mendes contacted immigrants in Weimar and invited them to her studio. They were asked to bring something that represents God for them in an abstract way. "I was interested in crossing the idea and terms of otherness/ the "being different" with those referring to immigration and spirituality."

During realization of this series, she met a 17-year-old girl from Afghanistan, who told Mendes her story. The treatment of this contact can be found in "Dance Play" (2013), a performance about movement, change, life and immigration. The play tells the story of a girl who comes from Afghanistan to Germany. "She walks slowly, because she comes from far away. If she does not have to run away, she will dance, for dancing is movement, life and strength for her", explains Mendes. The story finds expression through a poem, in which "Nike-Shoes" empathize with the history of the immigrant. The original performance of "Dance Play" won the Jury Prize Sophiensaele at the festival 100% Berlin in 2013.

Concurrent with these projects, Mendes developed several short films and video performances on ideas about God: in the video "Purification" (2010) Ana Mendes filmed an elderly woman one morning in a church in Lisbon, before the rush of visitors. The woman cleans the floor in a reverent way – for her the church itself seems to be God. In "Why I Like God" (2012) Ana Mendes bakes bread – a metaphor of the idea of God.

Shiblee Muneer from Lahore (Pakistan) is member of the Patayla-family of miniature painters and a teacher at the National College of Arts in his home town. It is the only institute worldwide where the labor-intensive technique is still taught in the traditional way. Muneer visualizes contemporary subjects, but technically and formally his work is based on classical book and album painting, an artistic practice that was very popular in the 16th and 17th centuries, the era of the Great Moguls on the Indian subcontinent. Muneer treats the role of media in society; their permanent presence and propaganda-like strategies are characterized by a violence that has a psychological effects on humans, making them restless and troubled. Muneer gives expression to related questions and doubts by means of his artwork. In regard to his series of thirteen miniature paintings “Neo World Order”, Muneer says: “I do not only exercise miniature painting in order to conserve a family tradition; perhaps I just continue an action which is natural to every human being, in order to animate the understanding and consciousness of a future generation (which is equipped with all the characteristics of this certain age). Through conceptual, formal and social, perceptual ways, the matter of my recent works pivots around the ‘idea of miniature painting’. I am studying the ‘royal code’, the ‘royal cipher’ of visual ethics (miniature painting), in order to find new ways, so that I can produce a comparable visual heritage with strong iconic impact while using the materials which are available now, during my lifetime”.

Besides the two paintings “The Idea of Beauty” (located between the two windows) Shiblee Muneer shows another thirteen-piece series in the exhibition. In relation to his “Corrupted Mystical Sounds” Muneer explains: “My work deals with my life experiences and how I survive all the cunning, crafty regulations that expose me and make me vulnerable. How am I supposed to comply with these orders and duties, which come through our lives, whether they are perceptible or not, and where I find they are the last word and I no longer exist. My work is my own world, where I try in a humble way to present my ideas (this is why I use lines – a minimal source and reference for visual action) in metaphorical ways, in order to give expression to my thoughts. For me every line incorporates a galaxy of significance, rather than a rigid word. Throughout my works I bring an aspect to discussion, which I call the ‘order of the vivid’ and which can be studied and received in spiritual, religious or sociopolitical ways. It is about how human beings (horizontal lines) – social animals or fleshly Gods – cope and play with an ethical order (vertical lines). This conflict, this movement creates a sound, which sometimes echoes in the sphere of our social belief and trust. I consider myself as someone who looks inside this holy dispute (which can only be named ‘Corrupted Mystical Sounds’) from the side, out of an acute angle”. This series (also called “Math Pages”) shows the opposing aspects of Muneer’s art: simplicity and complexity, an attempt to visualize his sociopolitical, religious and personal thoughts.

As resident and guest in the Municipal Studio Building in Weimar, Shiblee Muneer planned to think about the circle as a perfect form for expression: “If you minimize a circle, the final result will be a point and without a point there won’t be any line”, explains Muneer. Furthermore, he wanted to study the pictoral-artistic means and meanings that characterize the point’s journey, before it becomes – as a circle – significant as a metaphor of God. Muneer studied whether there is a credible substantiation for this simple geometrical form in visual language. Tragically, Shiblee Muneer’s father became gravely ill shortly after the artist had started his residency in Weimar, so he had to return to Lahore and cut short his stay – which had already been shortened because of problems acquiring a visa.

When trying to come to Germany for the installation of the exhibition “Believe It or Not”, Muneer was prohibited from leaving Pakistan by the German embassy in Islamabad – officially because of a “suspicion of commencing to work illegally”. For this reason and because of the very high prices of shipping art in Pakistan, we can (unfortunately and as an exception) only show copies of the drawings and miniature paintings that Shiblee Muneer planned to show here in Weimar, if he had only been granted access to Germany. The documents of the visa application correspondences between Muneer and German authorities are exhibited in the showcase in the event room of the gallery. Muneer planned to travel together with his wife Noreen Rasheed, who is also an artist and sometimes works together with her husband. In the end, the producers of this documentation that has been designated as art, entitled “Image makes Reputation”, are Shiblee Muneer and Noreen Rasheed in collaboration with the German embassy in Islamabad, the ACC Galerie Weimar and the bad, fabricated reputation of Pakistan. The media of the work are: black and white history, a hypothetical approach and authority.

Beneath the glass cover of a large table you can find numerous pictures inviting you to linger in front of some examples from Muneer’s oeuvre as well as the history of Pakistani miniature painting. Some of the collected copies show reproductions of historic Pakistani art, some show historic miniature paintings and other paintings were conceived and created by Shiblee Muneer under the influence of sociopolitical and historical experiences.

In her research project “FOR GOTT EN” (2011) the South Korean artist Chan Sook Choi asks age-old and recurrent questions of doubt and faith: Why does God remain silent? How can God be kind and allow so much sorrow at the same time? Answers to these questions can be found in different eras, starting from the Old Testament – Choi refers here to the book of Habakuk – to contemporary literature, for example in “A Grief Observed” from C.S. Lewis. On the search for very personal answers, Choi (as a resident of the International Fellowship Programme Studio14) interviewed three (initially five) women between the ages of 60 and 95 living in Leipzig. She invited the women to go with her on a journey through their life memories. For this purpose, she created the sedan chair “your eye is a window of your body”. The sedan chair, a historic vehicle for dignitaries, can be seen as a symbol for Choi’s appreciation of her protagonists. Here, the women took a seat to encounter their past – through their own words and images. Choi recorded this process of remembering. From the filmed material, Choi developed a parallel portrait. A book accompanies the mixed-media-installation; it documents the development of the project and enriches it with further perspectives. In this book, other people involved in the research project get a chance to speak. The sedan chair, videos, book and text are engaged in a dialogue about believe and doubt, forgetting and grief. The question of what it means to be forgotten (by God) repeats itself, for the question itself is constantly being forgotten (by God), says Choi.